Time to Sphinx

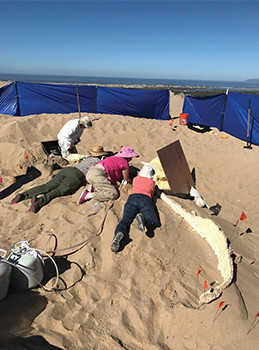

Spray Foam Magazine – Fall 2022 – In the 1920s, Cecil B. DeMille, the American filmmaker and director, was scouting locations to film The Ten Commandments (1923). Due to budget constraints, he had to abandon his vision of filming in Egypt and instead, pursue regional locations. DeMille emphasized production value and detail in his movies and was determined to find a way to meet his vision within his allotted budget. He found a suitable location in the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes, CA, where he proceeded to build the largest set-in movie history.

This elaborate set included 21 giant reclining sphinxes, mythical creatures with the head of a human, and the body of a lion. These incredible statues lined the entrance path to an 800-foot-wide temple.

This huge set was too expensive to transport, but DeMille was determined not to leave the treasured set for competing filmmakers to steal. Instead, DeMille ordered his crew to push the set into a trench and bury it in the sand.

To this day, it is still one of the largest movie sets ever built and still has great influence on many movie directors. Hollywood historians were determined to preserve this piece of American cinematic history for future generations to appreciate.

The many sphinx and set pieces lay hidden in these sandy tombs for 90 years until Peter Brosnan, a documentary filmmaker, showed interest in the site. He spent 30 years trying to raise awareness and funds for his documentary project, The Lost City of Cecil B. Demille (2016). »

In 2002 Amy Higgins, a historic plaster specialist, pieced together two, plaster bas-relief pieces to rebuild the Pharaoh’s head and hand. This piece was used by Doug Jenzen and the Lost City team to bolster future fund-raising efforts.

In 2012, Doug Jenzen, a historian, became the new Executive Director of the Dunes Center. He clearly understood Peter Brosnan’s vision and diligent work on this project and immediately began vigorous fund-raising for the excavation of DeMille’s historical set. Jenzen remarked, “I feel like I built upon the early work that Peter completed. I fundraised like crazy for the 2014 excavation, at which time we discovered the sphinx that we continued to work on for the following years.”

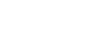

Jenzen arranged to have the Guadalupe Dunes site meticulously searched for set artifacts by archaeologists from Applied Earthworks, including lead archaeologist, Colleen Hamilton. The team was joined by two art restorers and museum exhibit specialists, Amy Higgins, and Christine Muratore.

The work was restricted to October each year due to its proximity to the snowy plover nesting area. Higgins commented, “The team dug in the sand dunes three times over the span of five years. Each time, we had increased success in finding larger and more dynamic pieces of the plaster sphinxes.” One of the discoveries in 2012, included uncovering a Pharaoh’s head and hand.

On the last day of the 2014 excavation, the team uncovered an impressive intact sphinx. Due to the timing of the discovery, the team was only able to preserve the right side of what they roughly estimated to be a 12-ft long, 14-ft high sphinx.

The team returned to the Guadalupe Dunes site in 2017 to continue to excavate the chest and six-ft high head. To say that the archaeological team was pleasantly surprised about the condition of the head is an understatement.

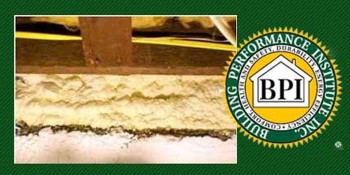

Spray foam aided in the conservation of the 300-pound sphinx head during the excavation process. The excavating team applied HandiFoam to support the plaster as they were brushing away the sand.

However, there was one major problem: the sphinx could not be removed without causing some serious damage. The plaster in the dunes was wet and too fragile to move.

Documentation and excavation proceeded at a slow pace, culminating with the removal of the plaster fragments of the sphinx during the last four days of the dig. The team needed to find a fast solution to remove the sphinx without causing further damage. This led them to investigate spray foam.

After finding out the basics and the possibilities of SPF, the restoration team contacted the technical department of HandiFoam for nontraditional applications. Their technical team recommended HandiFoam’s FOMO 605 F/R II, E84 Fire Rated Kits.

The team proceeded with the HandiFoam FOMO 605 F/R II, E84 kit which has a 3 lb. density. The closed-cell compound will expand roughly 20 times to form a rigid mass of foam. In the studio, art restorer Amy Higgins would spray the foam in a bag to support the plaster, later stating, “Of course, some foams don’t cure in a plastic bag without air, so experimentation proceeded.”

Conservators for artifacts recommend using reversible methods and products to avoid damaging a historical piece. Elmer’s white glue is a reversible product but needs to be supported during its long drying time. Traditionally, Paraloid B-76, an acrylic resin dissolved in acetone, is used as a strong adhesive with cheese cloth to support items when they are being transported. This proved insufficient for the weight of the plaster being excavated. So, the team thought, “Why not use spray foam in the field?”

On prior projects, the team had used spray foam to support dried plaster for display purposes. For this project, they decided to use it in the field to support the plaster as they were brushing away and excavating from the sand.

The team used SPF as a conservation method for a few reasons. Higgins shared, “First, and perhaps most importantly, it was the only material that we could find that would fill, adhere, support, and take the shape of the hollow statuary. Secondly, off-gas and therefore is safe for people and artifacts in the museum environment. However, it was a difficult decision given that spray foam is not a typical, archival material used to stabilize artifacts.”

The challenge the team had of excavating the plaster statuary from the sand dunes is its fragility. To create a museum quality exhibit, they needed to figure out how the pieces went together, like a puzzle, and then secure them to remain together for display.

The sphinx currently on display at the Dunes Center has “May 1930” carved into the side of it, which tells us that it was exposed for at least seven years after filming.

When piecing together plaster shards, they had to create an under-structure to support the pieces while attaching them together. The moist ground made even the thickest pieces of plaster fragile and soft to the touch.

Using soft bristle brushes, the team removed the sand inch by inch. Higgins would then apply spray foam on the back side of the revealed three inches of plaster before removing more sand. She also began embedding wood ribs into the foam, creating a skeleton to support the plaster from the reverse side. They were then able to work from the inside of the sphinx.

One of the strange parts of this story is that sphinxes from the film were subsequently transported to random locations. Two sphinxes graced the entrance to the Santa Maria Golf Course and disappeared for reasons we can only guess. Other sphinxes decorated private properties and served as grandiose lawn ornaments. (Photo credit: Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Center).

The excavation of the sphinx paw and arm took time and precision. The team first outlined the paw and forearm buried upside down in the sand. They then carefully removed the sand from the inside of the piece and created a wood skeleton to support the plaster and act as handles to move the piece from the dunes. Just being exposed to the air for a day, the plaster had a chance to dry somewhat. Higgins then sprayed foam inside to attach the wood skeleton to the plaster. The team then slowly removed the sand from the outside of the paw and arm and carefully lifted the arm and removed it from the dune. The team retained and documented the small pieces that fell off the top during this process, and then reattached them in the museum.

The conditions at the dig added extra challenges to the project. The technical experts at HandiFoam advised the art restoration team that the foam needed to stay between the temperature of 75° and 85° F. Early morning temperatures at the site could dip down to 50° F. Higgins wrapped the tanks in sleeping bags and created a lean to shed structure with a propane heater to keep the tanks warm in the cool early morning dew.

The team had to pack up this rig every night on a sled, since the protected dunes won’t allow motorized vehicles on site, to prevent the destruction of native wildlife habitats.

The team considered this use of SPF a huge success and proceeded in using the same method for the sphinx head and chest area. They were encouraged by the foam’s fast rigidity and stability after its cure time. It turned out to be the only material for the complexity of stabilizing the large, damp, fragile plaster in the dunes.

Jenzen commented on all the efforts put into this mammoth project saying, “If you asked me which portion of the excavation was the most difficult during the duration of this difficult project, I would have replied by saying, ‘whatever phase of the project we were working on at the time was nerve wracking.’ Including, fundraising, government permitting, avoiding endangered species, managing communications and media, watching irreplaceable statuary break during the excavation, and the restoration process all resulted in prematurely gray hair. Preserving a piece of history, promoting the community, and developing relationships with everyone involved and the old-time families made it meaningful and worthwhile.”

Even after the documentary The Lost City of Cecil B. DeMille was completed in 2016, Jenzen and his team continued the project to preserve a piece of Americana and promote tourism in the under-served farming community of Guadalupe. The head is now on display at the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Center, a natural history museum located on California’s Central Coast. Next year is the 100th anniversary of DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923), and what better way to acknowledge this epic movie than to review its history and the part SPF played in the recovery of the incredible set. Something to sphinx about!

Disqus website name not provided.