A Night at the Museum

Summer 2020 – Spray Foam Magazine – The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (designed by Frank Lloyd Wright) is situated in the Upper East Side of Manhattan known for its upscale restaurants, Brownstones, art galleries, museums, and parks. Opening its doors in 1959, the art museum has experienced cracking in the rotunda walls over the years, with numerous attempts to repair them. These past repair efforts were unsuccessful until 2005, when the museum’s board of directors committed to a major restoration aimed at not only repairing, but improving the building so that it would last for generations to come.

At the time of the restoration, Brendan Connell, director and counsel for administration with the Guggenheim said, “Every possible step has been taken to ensure this restoration has been done in a way that’s faithful to Wright’s design intent, but also faithful to modern developments and what we can do to create a better museum.”

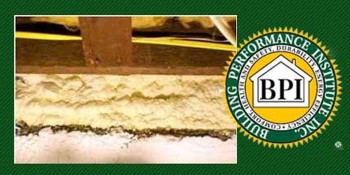

The key to the renovation, as with most buildings of such high historical importance, is that the appearance of the building cannot be changed, inside or outside. Building science expert, Bill Rose of William B. Rose and Associates, collaborated on the design of the energy upgrade recommending closed-cell polyurethane foam as the material for upgrading the existing insulation. This particular insulation was recommended for its ability to reduce moisture migration and maintain safe relative humidity levels to preserve the art stored and displayed in the structure. Fiberglass and cellulose were not options for this particular project because these materials are not vapor retarders and did not provide the highest possible R-value in the available space inside the wall and roof slope cavities. Bill Rose recommended Building Envelope Solutions, Inc. (BES) as the installer for the project because of their experience in museums and other types of buildings with critical indoor environments.

BES was owned by Henri Fennell, a building envelope specialist and architect with over forty years of experience in energy conservation design, products, and services. His first spray foam insulation job was in 1971, and that experience led to his creating Building Envelope Solutions (with its FOAM-TECH Division). BES worked on the Guggenheim with a team of specialists including architects, contractors, engineers, and building science experts to assess and implement the repair methods. Fennell goes on to explain, “In addition to the three years it took to make the structural repairs, the renovation of the building's enclosure included updating insulation, windows, and mechanical systems within the building. These improvements saved energy and helped maintain a safe indoor environment for the artwork on display in the gallery.”

BES introduced the Guggenheim team to the cavity-fill (injection) method as a possible alternative strategy for the project. The use of the injection method in lieu of the original preconception that installing spray-applied insulation would require the removal and replacement of all of the existing interior plaster finishes, solved a number of problems for the art museum. First, the cost was significantly reduced because it required less labor (no demolition and replacement) and fewer materials (virtually no framing, lath, and plaster). Secondly, the existing rigid foam board could be left undisturbed and then encapsulated, rather than having to be removed and replaced. Saving the lath and plaster reduced the disturbance of the structure during the delicate concrete repairs, and it assured that the energy upgrades would not be visible in this historic structure.

The BES application team started the installation process at the top of the rotunda and worked their way down simply because it was easier to roll the equipment down rather than push it up the spiral ramp.

Photo by Ken Ohyama, FlickrWhen Fennell, who now owns H C Fennell Consulting, LLC, proposed the more cost-effective and non-intrusive injection solution for areas that were not already open for a spray application, he had to prove the concept to the very conservative Guggenheim design team. To prove this approach prior to it being used for the full-scale work, BES had to demonstrate that filling cavities through holes would work consistently. Fennell accomplished this demonstration in an emergency session in one of the gallery’s roughly 60 wide radial bays that had a serious condensation problem where water damage was occurring due to uninsulated gaps (thermal bridging) in the insulation at the wall-to-floor transition.

BES did this by arriving one night after closing time with a slow-rise portable kit and injected the bottom foot of the wall with foam. The museum personnel protected the artwork before BES technicians carefully drilled 3/8-inch holes in the plaster (one per bay) and injected the foam, filling a cavity that varied from three to six inches in depth up to the top of the thermal bridge locations (this was a minimum of six inches above the intersection of the wall and the sloped floor).

Following the injection work, BES used infrared thermography to show the design team how the cavity-fill process could be quality controlled in real time due to the exothermic heat of the closed-cell foam’s chemical reaction.

The next day, the museum opened in the morning as usual with no sign of the work that had been done the night before. The Guggenheim team reported that the condensation issue had been “cured.”

The insulation technicians jokingly named themselves “The Men in Black,” (after the blockbuster movie) as it felt like they were carrying out some covert night mission with their foam kit in a black rolling suitcase, black infrared camera case, and dark uniforms. Infrared thermography was also used later during the full-scale insulation session to verify that all of the cavities were full in each section of wall (the exotherm was easily visible through the plaster). The infrared videos were recorded and were then submitted to the museum staff.

At some point after BES left, the museum had the plaster removed in this one test area to compare the amount of foam by visual inspection to the amount shown in the infrared images.

In this way they confirmed that the cavity-fill method and the QA protocol were valid. With all of this impressive evidence, Fennell’s company was contracted to insulate the entire rotunda portion of the building.

Before beginning the injection foam process, the museum personnel had to protect the artwork.

Photo provided by Henri FennellOnce the museum was closed for renovation and the artwork removed and protected, BES proceeded with the full-scale wall and roof slope insulation in the gallery and the basement. All of the work areas along the exterior walls in the rotunda were on an incline, so BES had to use leveling platforms for work that required ladders.

The whole rotunda was also a continuous sloped ramp in the other direction, so the custom foam machine was mounted on a cart that had locking wheels. The first foaming session was at the normal museum ambient conditions (72 degrees F, 55 percent RH) with the full-scale insulation session at 70 degrees F and 35 percent RH (relative humidity) as there was no longer any art that required environmental protection.

There was no pressure to complete the work in a hurry and no risks were taken. The only real challenge was the excessive amount of time it took to drill holes in the steel lath (in the plaster) and to accomplish the basement work due to the HVAC equipment obstructions and the waterproofing coating on the foundation being messy. The parking and hotel costs in New York City were also an ordeal, Fennell emphasized. “We couldn’t park near the site, so everything had to be portable.”

The surface area of the entire project was about 15,000 sq. ft. of wall and roof in the rotunda and in the Aye Simon basement. In the rotunda, closed-cell foam was injected into the three to six-inch deep closed-cavity. In the basement, the column covers were injected with foam and two inches of rigid foam board and spray-applied foam were installed on the foundation walls between the columns. The test session only used about 20 pounds of slow-rise closed-cell foam (from disposable and refillable kits); the actual full-scale insulation in the rotunda used 1,500 pounds of slow-rise closed-cell foam which was injected into a closed cavity that was sheathed with wire lath and plaster on the room side. The old rigid foam board and concrete were on the exterior side of the cavity.

In the basement area, spray and rigid foam were applied to concrete previously coated with bituminous waterproofing. Thermax was approved by the AHJ in advance of this historic work and was installed on about 250 square feet of exposed basement walls.

Fennell called this method “knitting.” BES termed the work in the basement area a “submarine project” due to the large number of pipes, conduits, and other equipment mounted on the walls and ceiling that they had to work around and behind.

Fennell custom engineered the rolling cart using components from different foam equipment manufacturers to adapt to the requirements of the art museum. “You can’t pull a big truck up on the sidewalk outside of a famous museum in New York City.” Plus, the exterior repairs to the concrete required staging and a temporary protective cover which occupied most of the space on the sidewalks on three sides of the museum.

We basically had to test the equipment, break it down, ship it to the site, and reassemble it on site.” This custom cart was key to being able to perform the work in NYC. “Using a custom portable cart was something we had done on other remote-access projects like hotels, manufacturing facilities in high-rise buildings, islands, and lodges at the top of ski lifts, so it was not new for us.”

All of the components had to be operable using just 110-volt power, and the components had to be compact and easy to move and assemble inside the building. This project-specific portable system utilized nitrogen-pressurized refillable cylinders to supply the pressure for processing. Standard heated hoses were converted to 110-volt operation with step-down transformers.

There were 110-volt outlets periodically on the railing wall which were used for controls, heat, and to run the small compressor.

The technicians used an infrared camera to verify the tanks on the cart were at the required temperature and test shots were made which demonstrated the physical properties of the foam before they started the work.

At the beginning of the project, it was suggested that BES would begin working at the bottom of the rotunda ramp when they arrived with their equipment. Fennell, however, requested that BES be allowed to start at the top of the building and work down. The assembled rolling cart with the foam equipment on it was then easily maneuvered down the spiral ramp by one technician as the work progressed. Pushing it up the ramp would have been difficult and collecting enough workers for each move would have created interruptions.

BES technicians had their OSHA safety ratings and conducted toolbox talks on a daily basis. The technicians wore respirators during the full-scale insulation work. Fortunately, the ventilation rates in the large space were high, and the volume of foam material being injected into the confined wall cavities was relatively low (not atomized). “We used window fans to circulate escaping vapors away from the workers and toward the larger areas. Masks were worn for the plaster dust created while drilling,” confirmed Fennell. “The main walls were about eight feet high and we used staging with railings and locking wheels for the ceiling work above the lay lights and on the top floor.” The condensation issues in the gallery spaces and moisture migration into the concrete cast-in-place walls were eliminated due to the closed-cell insulation Fennell provided. By using spray foam insulation and adapting the equipment to a unique situation, these “Men in Black” really did save the day and the night at the museum.

Disqus website name not provided.